Jordyn Hrenyk

Jordyn Hrenyk

A Meditative and Reflective Practice

For Jordyn Hrenyk (she/her), beading has always been a way to relax and work through difficult issues in her day-to-day life. She first learned to bead from a friend and colleague in 2015 and has continued to hone her skills and learn new styles from whomever she can–from friends, elders, YouTube videos, and beading circles. Her investment in learning to bead has paralleled her educational journey and is now central to her doctorate dissertation.

The first style of beadwork she learned was brick-stitch, and she quickly made many “fringe” earrings for family and friends. In graduate school, she became interested in learning new beadwork styles particularly those traditional to her Michif community:

“I went to grad school really far away from my family in Ontario, and I was living there by myself, and I didn’t know anyone, and it was like a super conservative institution with hardly any Indigenous presence. I felt super lonely and just bad for myself. And I wanted to make my sister, who was super supportive of me, a nice Christmas gift. I wanted to learn how to do florals. That’s really important in Michif beadwork history. So I found a video. I had none of the right supplies. I actually beaded onto a paper towel. That was the backing that I used, and it worked! Looking back now, I don’t know how the whole thing didn’t just fall apart.”

Beadwork by Hrenyk. Courtesy of the artist.

An example of beaded Michif florals like those that inspire Hrenyk. Courtesy of the Cleveland Art Museum.

She framed her first beaded applique floral piece and gifted it to her sister. Since then, she’s continued to learn and bead, often for research purposes. Like her first floral piece, she doesn’t sell any of her beadwork. Instead, she gifts her artwork to those around her in appreciation and thanks for their role in her life. As a Ph.D. student at Simon Fraser University at the Beedie School of Business, Hrenyk studies Indigenous entrepreneurship. At the conclusion of the comprehensive exams phase of her Ph.D. program, she wanted to gift something to the three professors who supported her through this lengthy process:

“These professors each had to devote quite a lot of time and energy to this; in agreeing to take part, they each had to help me prepare for the exams, as well as write the exams specifically for me, and individually grade my performance. In order to thank them for their time and for investing in me, I created each of them a beaded circle.”

Hrenyk has beaded similar circles before as part of her research. Creating these circles has been a part of her process to understand the teachings and knowledge shared with her through complete meditation and reflection. The first time she made a concentric circle, she beaded for 11 hours straight, and, at the end, realized she had represented the story of her learning process through her beadwork. At the center of her dissertation is a study of Indigenous entrepreneurship, specifically entrepreneurship by Indigenous beadwork artists. Her dissertation research led her to Carrie Moran McCleary’s virtual beading group:

“She [Carrie] and all of the other beaders in this group are full of joy and laughter and have always encouraged even less confident beaders like myself to be proud of the work we're creating. Everyone has always been so generous and generative; beaders at bead night always tell the truth but are never judgemental and they always help you to see the best in your work.”

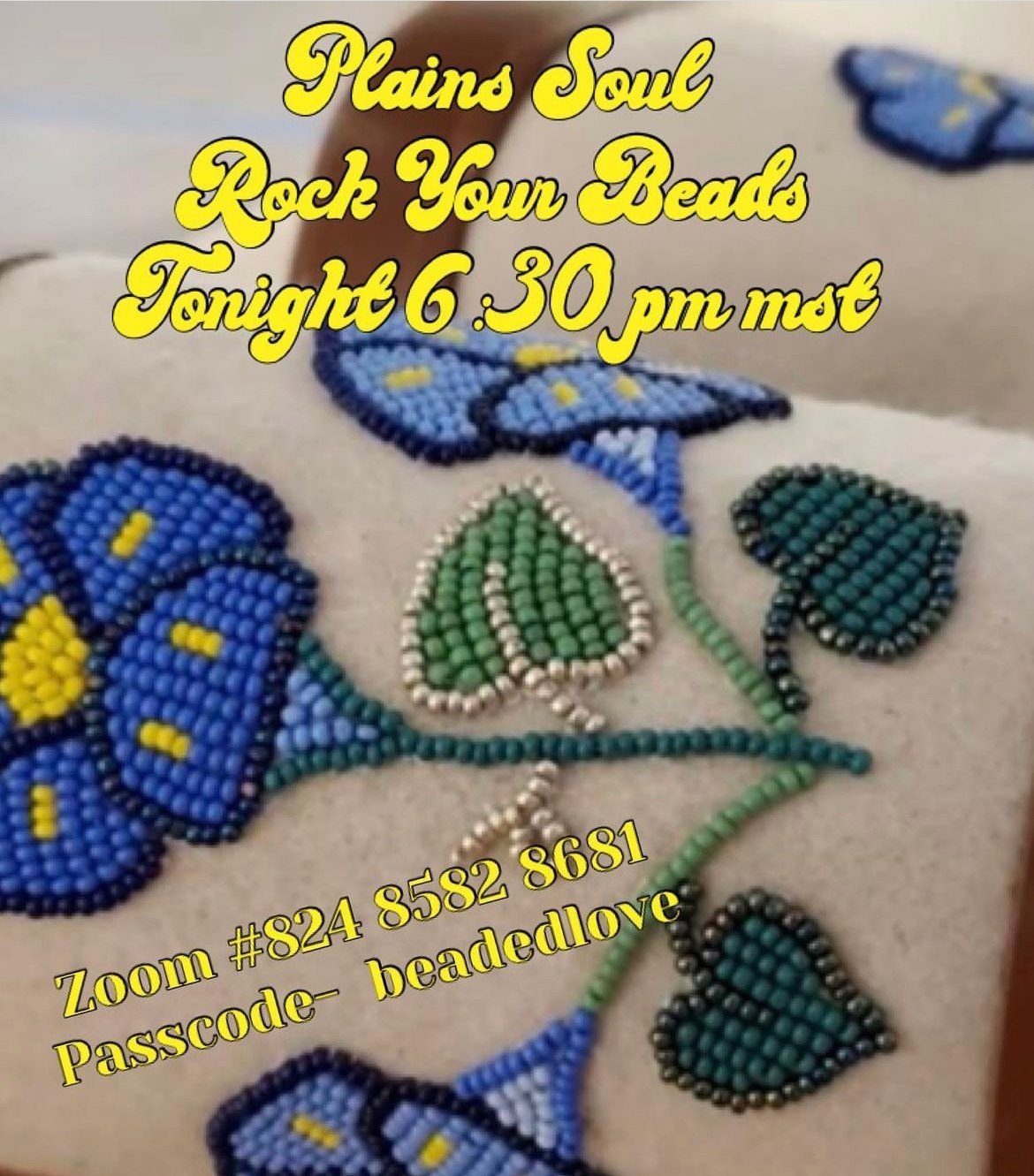

By joining beading circles like those hosted by Plains Soul, she has had the opportunity to learn from and speak with artists across North America who sell their beadwork. Through this research process, she’s learned about individual artists’ communities’ unique connections to beadwork. Many virtual beadwork circles started or ramped up during the COVID-19 pandemic, which, Hrenyk believes, has resulted in a really unique time for beadwork.

Bead Night Instagram Post. Courtesy of @PlainsSoul

“We’re in such a unique moment for beadwork right now. Even through the pandemic, especially. All of these connections that are happening across boundaries that, it turns out, were never there. But we never accessed each other. We never found community this easily. I know a ton of beaders who beaded when they were young and stopped, but during the pandemic picked it up and have found a lot of community through the pandemic and since.”

Through her research, Hrenyk has also had the opportunity to learn more about her own community, the Métis’, relationship with beadwork. Many Métis have historically relied on beadwork as a source of income and financial stability–exactly the relationship to beadwork that she studies. Her own relationship to beadwork as meditative and a research practice as well as her research of Indigenous entrepreneurship demonstrates the many and varied types of beadwork and relationships to beadwork held by Indigenous communities across North America. Through her work, both beaded and scholarly, Hrenyk makes a unique and significant impact, particularly through her contributions to the often overlooked field of Indigenous entrepreneurship.

Artist Biography

Jordyn Hrenyk is a Michif beader and researcher, currently completing her Ph.D. focused on Indigenous artisan entrepreneurship at Simon Fraser University at the Beedie School of Business; she currently lives on Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Territory. Jordyn was born on her home territory in Treaty 6 (Prince Albert, Saskatchewan) but grew up in different urban centres in what is currently called Canada. Jordyn’s Métis family names include Smith, Boyer, Ferguson, Cardinal, Parenteau and Bousquet. In her dissertation, Jordyn is working with Indigenous beaders around so-called Canada and USA who create and sell beaded works to try to understand how markets of Indigenous entrepreneurs become supportive communities. Jordyn learned to bead from a friend and former coworker in 2015 and beading has been an important part of her life since then. As a Ph.D. student, Jordyn often includes beading as part of her research processes.